The Swedish data retention directive became part of Swedish law May 1st 2012 and ever since Swedish internet providers have stored intrusive information about internet connections.

The point of the directive is to ensure that information about communication is stored so that various agencies can access the information for their investigations and prosecutions of serious crime.

Internet service providers are forced to store data that are necessary to:

- Track and identify a source of communication

- Identify the end destination of a communication

- Identify the date, time and duration of a communication

- Identify the users' communication equipment, or the equipment they re believed to have used

- Identify the geographical location of mobile communication

Read the Government's regulation on what data to store to get a detailed view of which information they are expected to store about their customers.

History surrounding the data retention directive

Everything began 10 years ago when Great Britain, France, Ireland and Sweden submitted a suggestion on the 28th of April 2004 to the Council of Ministers regarding a general duty to save traffic data for all service providers of electronic communications services.

The proposal was met by a great deal of opposition from, among others, the European Data Protection Supervisor, who considered the proposal to be a violation of personal integrity and that it was not compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights.

The proposal was rejected and was on ice until the London bombing of 2005 when the Council of the European Union called on the Commission to prepare a new detailed proposal.

On March 15, 2006, a modified version of the proposal became the official data storage directive, stipulating that EU Member States should transpose the directive into national law by September 15, 2007 regarding telephony, and on March 15, 2009, regarding Internet access.

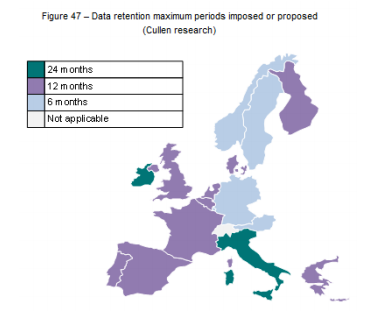

The directive allowed each Member State to choose a storage period between 6 and 24 months, with Sweden choosing 6 months.

Below is a summary of the storage period of EU Member States.

Sweden appointed a government inquiry to begin work on national legislation.

The state investigation was published in November 2007 (SOU 2007: 765) and contained a complete proposal on what the legislation could look like for storing traffic data.

On March 15, 2009, the Data Storage Directive came into effect, but Sweden had not yet implemented it. As Sweden did not implement the directive in time, the EU Commission initiated a lawsuit against Sweden in April 2009.

Then followed a time of waiting for the government's proposal for transposition of the EU directive. The time for the introduction -- according to the directive -- was passed and in December 2010 the government submitted bill 2010/11: 46 to the Riksdag.

The bill was accepted, and the date of introduction of the Data Storage Directive would have been on July 1, 2012. But since Sweden risked financial penalties for not implementing the directive on time, they instead chose to implement the directive on May 1, 2012.

In a verdict on May 30, 2013, Sweden was convicted of breach of treaty because the Data Storage Directive was not implemented before 15 March 2009. Sweden was ordered to pay an amount of EUR 3 million to the European Commission.

On April 8, 2014, the EU court annulled the controversial data storage directive, and two days later the Post and Telecom Agency (PTS) announced that no action would be taken against operators who stopped data storage.

Several operators stopped storing data about their customers.

Economical effects due to the Data Storage Directive

The Data Storage Directive has entailed large investment costs for the operators. Various calculations have shown costs ranging from SEK 200 million to just over SEK 800 million.

The EU directive does not regulate how the costs incurred as a result of the directive should be allocated, but allows each Member State to decide it by themselves.

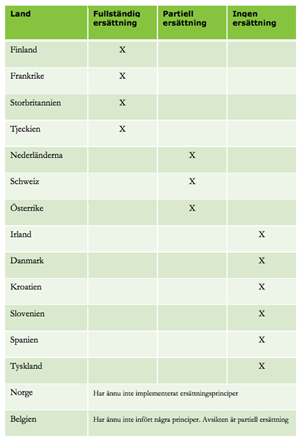

Below is a table of how different Member States have decided to compensate operators for the expenditure linked to the Data Storage Directive.

Operators in Sweden receive compensation for providing information that has been stored about their customers. The compensation is based on the costs of the necessary technical systems and personnel costs.

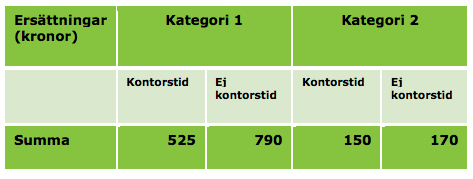

PTS has created two different categories for compensation. The first category, category 1, is cases where the operator must perform a "technical investigation to supplement the set search parameters required to be able to search for requested data" - PTS-ER-2013: 24 p.31

The second category includes cases "where a technical inquiry does not have to be carried out by the storage person, such as disclosing subscriber information or telephone call lists for a certain period of time" - PTS-ER-2013: 24 p. 32

The second category includes cases "where a technical inquiry does not have to be carried out by the storage person, such as disclosing subscriber information or telephone call lists for a certain period of time" - PTS-ER-2013: 24 p. 32

The compensation that the operators may receive is based on the category of the case and whether or not the case occurs during working hours. Below is a summary of how compensation is structured.

The operators thus receive a compensation of SEK 150-790 each time a legislative authority wants to request information about a citizen.

Data storage continues in Sweden

After the Court of Justice annulled the Data Storage Directive, many operators stopped storing information about their customers. Bahnhof, Tele2, Bredbandsbolaget and Telenor quickly announced that they have stopped storing the data required by the directive, and that they have erased all logs for the past six months.

Unfortunately, the suspension of data storage did not last long because on April 29, 2014, Beatrice Ask appointed an investigator to examine how the European Court of Justice's ruling affects Swedish legislation.

On June 13, 2014, the results of the rapid investigation came, and according to the investigation, Swedish law does not violate EU or European law.

After the investigation published its results, the Swedish Post and Telecom Agency issued a decree on June 16, 2014 that it will take regulatory measures against operators who do not comply with the law.

All operators except the Bahnhof have again started to store traffic data. Bahnhof requires that the case be tried legally before they begin data storage.

David Wibergh